![]()

![29f7c043f76a2bde437fd0d52a185152]()

Quote:

The wag who first suggested running the trailer for Bad Education before screenings of The Passion of the Christ in southern France deserves a rosette for provocation beyond the call of duty. But while the region’s priests have responded with predictable outrage, they should have taken a closer look at the film itself. To the character of the paedophile Father Manolo, Pedro Almodóvar extends the same compassion and pity with which he regarded the various sex offenders in Matador (1986), Tie Me Up! Tie Me Down! (1989) and Talk to Her (2002). Almodóvar has the most democratic sensibility in cinema since Andy Warhol. Whatever passes before his camera is met with curiosity or understanding.

This creates some unusual difficulties in Bad Education. The slow-motion footage of pubescent boys frolicking in a river invites us to see the children from Manolo’s perspective, when in fact he is not observing them at that point – the erotic reading of their horseplay belongs uniquely to Almodóvar. Similarly, the movie’s most hypnotic image – an overhead shot of rows of white-vested boys exercising in the schoolyard – would be problematic in its echoes of the homoeroticism of 100 Days Before the Command (1990), Like Grains of Sand (1995) and Beau Travail (1999), even if it were not the case that, once again, it is Almodóvar, not Manolo, who is investing the children with sexual properties. Unless, that is, the elevated camera hints that a higher power is complicit in this voyeurism, an idea that surfaces in comic form when a priest who is reminded that God has witnessed his wrongdoings remarks: “Yes, but He’s on our side.”

If the Catholic church is not placated by the film’s generosity toward its errant servants, it might take consolation from the fact that Bad Education is more concerned with the traffic between past and present, life and art, sin and forgiveness. From its credit sequence, which plays like Saul Bass animating a Gilbert & George catalogue defaced by Joe Orton and Kenneth Halliwell, the film aspires to the texture of a collage or mosaic. It’s there in the layers of faded, half-peeled movie posters outside the derelict Olympo Cinema, where the boyhood friends Enrique and Ignacio once masturbated one another as Sara Montiel loomed on the screen before them.

And you can see it in José Luis Alcaine’s deep-focus photography and Antxón Gómez’s art design, particularly in the office of the adult Enrique, now a successful film director. Ignacio arrives there clutching a story (‘The Visit’) based on their school days, while around them the segmented background and foreground compete in an ongoing and symbolic war of mise en scène reminiscent of The Bitter Tears of Petra Von Kant (1972). Mosaics are most strongly represented on the exterior of Ignacio’s apartment building, with the same patterns inside on the walls and curtains. The suggestion in these mosaics of a gaily coloured puzzle, of unruly pieces put together without ever quite fitting, could not be more appropriate.

Then there are the characters’ slippery identities to contend with. In Enrique’s film of ‘The Visit’, Ignacio hopes to play the transsexual Zahara, whose real name is Ignacio, who in turn poses as her own sister to confront her abuser, Father Manolo; Ignacio himself goes by the name of Ángel, but is later revealed to be Juan, brother to the actual Ignacio. Some characters, like Zahara’s friend Paquito, don’t actually exist outside ‘The Visit’, while others, such as the leather-jacketed Enrique with whom Zahara has sex, are alternative incarnations of characters we have already met. Scenes from ‘The Visit’ are played out as flashbacks, though they are no more definitive in their version of events than the erroneous account of Ignacio’s death that is corrected when Father Manolo arrives under his real name, Berenguer.

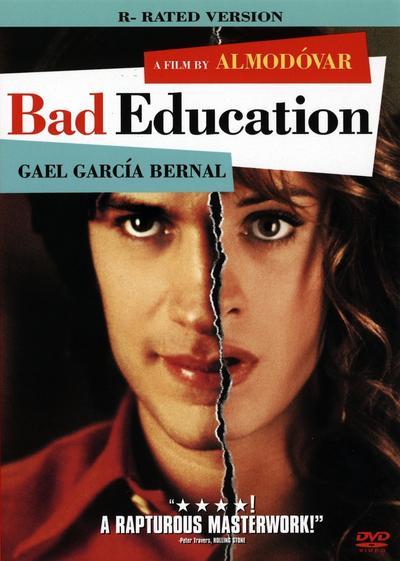

Any description of the plot, which incorporates flashbacks within the film within the film, risks becoming a pointless itinerary. When a film-maker exercises this much control, there is an enormous gain, but a small loss too. And for all its authentic Almodóvarian passion, the movie sometimes resembles a clinical experiment in storytelling. The most potent antidote to this is the miraculous four-sided performance by Gael García Bernal, who plays Zahara as well as Juan-playing-Zahara, Juan-posing-as-Ignacio, and plain old Juan. Bernal not only looks divine in everything from platinum wigs to retro sportswear, he also displays an emotional dexterity to match his frequent Gaultier-designed costume changes. When the film gets in a spin, Bernal is its compass.

Without him, the movie’s symmetry and self-reflexiveness could have squeezed the life out of the material. Moments that provoke a strong connection are likely to be those that have the most clarity and simplicity – Manolo’s hunt for Enrique and Ignacio in the school dormitory, or the subtle editing that articulates Ignacio’s abuse (to the heartbreaking strains of ‘Moon River’), or the fraught poolside scene in which the adult Enrique is silently rebuffed by the man he believes to be Ignacio.

These episodes are marked by a spare visual style, an emancipation from physical clutter, and the characters themselves are on the same quest to strip away unnecessary embellishments. Audiences who find themselves short of breath during parts of Bad Education, as on a climb to high altitudes, will notice a shift in the final section, which peters out quite deliberately, like All about My Mother (1999) and Talk to Her before it. As the truth about the demise of the real Ignacio comes to light, the movie lets out a sigh of resignation; the multi-layered facade that had kept us entertained for nearly two hours is packed away, literally during the scene in which the camera retreats from a movie set as the lights are extinguished one by one. Truth brings its own rewards to the characters, but for Almodóvar it also represents a small death. In the final image, Enrique clutches Ignacio’s last, incomplete letter and slumps against his gate. The eye can’t help but experience a kind of anti-climax as it registers the first plain shot in this whole vibrant movie. Ryan Gilbey, Sight and Sound, June 2004

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

http://www.nitroflare.com/view/3E9D44FE4F0D104/Pedro_Almodovar_-_%282004%29_Bad_Education.mkv

Language(s):Spanish, Latin

Subtitles:English